The Technology Entrepreneurship Office (TEO) is one of many entrepreneurship resources on campus. Dan Olszewski is a skilled entrepreneur and the director of the Weinert Center for Entrepreneurship, which is part of the Wisconsin School of Business but assists students across majors with entrepreneurial education, activities, competitions, and programming.

Professor Olszewski received his undergraduate degree in economics and computer science at UW–Madison, then went on to earn an MBA from Harvard and become a McKinsey consultant. He gained direct entrepreneurial and acquisitions experience with a $450m company. Realizing his interest in teaching, Professor Olszewski joined the UW–Madison faculty and has been part of the business school for the last 20 years. He is also the co-founder of the Morgridge Entrepreneurship Bootcamp, which is a one-week intensive training program in technology entrepreneurship of particular interest for College of Engineering graduate students who might already be involved with TEO.

But what is Professor Olszewski’s advice for what comes after training, when you have an idea that you’re ready to bring to the market? We asked him about the Business Model Canvas (BMC) and how correctly applying it can help you ask the right questions about your innovation and deliver not only valuable tech, but a sound startup ready for success.

How is the Business Model Canvas different from a business model, and why might that understanding be important to aspiring entrepreneurs?

Prof. Olszewski: The term “business model” actually has a lot of different meanings, and that was probably one of the issues. If someone asked an entrepreneur to show their business model, they might wonder what exactly they wanted—a spreadsheet? Profits and losses?

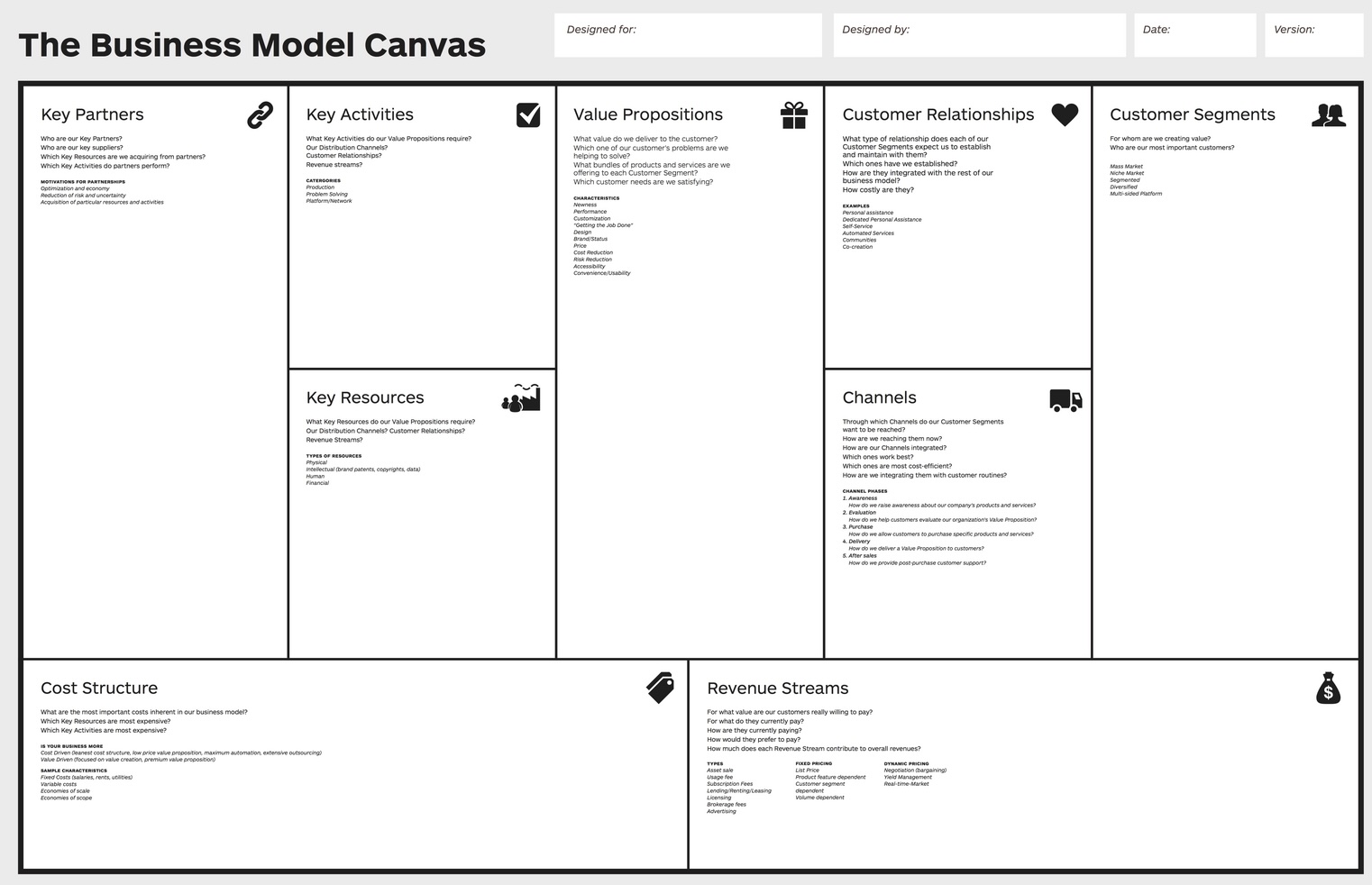

The BMC was a collaborative innovation to determine what is really important in a business model. It created a nine box canvas with numerous iterations, which has become the industry standard in entrepreneurship. Now, when someone asks for your business model, you can actually go through these nine boxes or even put up the canvas—I’ve been at various startups and they’ll actually have their business model printed out on their wall with post-it notes explaining it.

The BMC has nine different boxes with hypotheses about what your business is. If you’ve validated or invalidated those hypotheses, then you’ll have a pretty good idea of what your business model is and what your business entails. And more importantly, you can efficiently communicate it to someone when you’re explaining your business idea.

What are the key elements of the BMC that work well? Are there any pitfalls to avoid if you apply it incorrectly?

Prof. Olszewski: I would say the most important aspects of the BMC, especially for an early-stage entrepreneur, are the target customer segment and the value proposition for that target customer segment. That’s the crux of the BMC and where you want to start to iterate on it, because if you don’t get that right, I’d say the rest of the business model is going to be built on a very weak foundation.

That is quickly followed by the revenue stream of how you get paid. Because there are lots of ideas where there’s a customer and value, and it could be very beneficial, but at the end of the day, a company needs to get paid. Figuring out how that’s going to take place is another one of the real critical questions to answer in your business model.

It’s also very important that the entrepreneur realizes this is intended to be a living, flexible document. You don’t have to put these things down and set them in concrete, or think, “I’m sure I’m right.” It’s quite the opposite. As you gain new learning, new information, you have to be willing to pivot and change. That is one of the reasons that they often say you want to use post-it notes so that it’s very easy to change when you learn something new and you realize, for example, that value proposition doesn’t actually resonate with that target customer. I’ve discovered a different value proposition that they do care about. It is very much intended to follow a scientific approach to experimentation.

How does understanding the BMC ultimately create a better startup or business?

Prof. Olszewski: Firstly, a canvas allows you to communicate what your business is. Numerous times, I’ve met with students who want to tell me about their idea, and at the end of 30 minutes, I still really don’t know what their idea is. They would be talking all about the technology, they’d be showing a website, they’d have all kinds of information that they were imparting, but it wasn’t giving me an understanding of: what is your business?

I tell them to fill out the canvas and then we’ll meet, and at that point we’ll have a much more productive conversation on what the business is. You can get better feedback that way.

A BMC is also more flexible. We used to have students write a 50-page business plan that they’ve spent all kinds of time on. These were actually very difficult to make changes to, because when you realized you didn’t have the right target customer, you can’t just do a global replace on it; you have to go through the 50 pages and rethink the logic and all of the references. Students would fight making changes—even though they should—just because it was difficult. Whereas the BMC makes it very easy for people to pivot, to make those changes as they learn something. They then write a business plan later in the process once they feel enough confidence, versus having it be one of the initial steps.

What are your top tips for entrepreneurs in TEO looking to learn more about applying the BMC to their tech innovations?

Prof. Olszewski: My first tip would be: don’t view all nine boxes as equally important for every idea. I would say that the three I mentioned—value proposition, target customer, and revenue stream—are universally the most important ones. Then, depending on your idea, some of the other boxes may be more or less important. Adjust your effort accordingly.

Second, the foundation is built on the customer. We call it “product-market fit,” which is how your value proposition aligns with your target customer. That foundation is really important, so you’ll want to have a high degree of confidence in it before you spend a lot of time building out your financials and other components.

Third, be very willing to pivot and use this as a starting point for your idea, but don’t expect your initial idea to be your ending point. You’re almost assuredly going to learn as you go through the process by talking to customers, running experiments, and you’ll have pivots along the way. Embrace those. Don’t view them as failures—view them as learning opportunities to get you closer to the right answer.

• • •

Feature image: Dan Olszewski at the Weinert Center for Entrepreneurship 25-year celebration in November 2024. Photo by Paul Newby II.

Written by: Bri Meyer